#3

Night and Fog

Re-Encounters with a Film

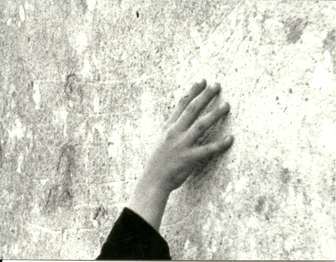

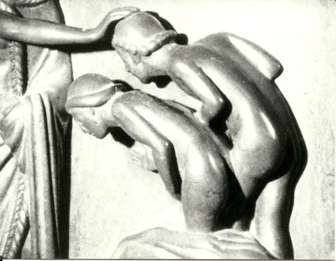

No other film became as influential for the retroactive awareness of the extent of the German concentration camp system as Alain Resnais's Nuit et Brouillard (Night and Fog). The screening of the film at the "3rd West German Cultural Film Festival" in Oberhausen on 24 October 1956 was one of the first in Germany. It stood at the beginning of a long history of reception that took very different courses in different countries and was invariably reflected in the respective translations of the original text by Jean Cayrol. To kick off the re-selected project, the two versions of the film that are in the festival archive were shown for comparison in Oberhausen in May 2018: a 35mm print of the French version in colour and black-and-white and a 16mm black-and-white print of the German version, which in this form became a staple object for political education in West Germany. In the GDR, however, a version produced by DEFA with a different translation was available from 1960. In the further course of the re-selected project, comparative screenings of the two German versions took place in Dresden (2019) and Leipzig (2021), reminding us that conflicting memory policies were and are also part of German history.

With a text by Tobias Hering and a text comparison of the German versions, re-selected Dossier #3 - Night and Fog illustrates the importance the film had for the conception of the ongoing archive project of the Short Film Festival.

Seeing Again

Nuit et brouillard – Nacht und Nebel – Night and Fog

by Tobias Hering

The following text was written as an introduction to the double screening of the French and German versions of Alain Resnais's 1956 film, Nuit et Brouillard (Night and Fog), at the 64th International Short Film Festival Oberhausen in 2018. The screening took place in the Gloria theater of the Lichtburg cinema in Oberhausen on May 4th, 2018, and was attended by approximately one hundred people. It was also the public inauguration of the “re-selected” project. At the core of this project lies the idea that the history not only of each film but of each print is rhizomatically connected with and entangled in the histories of its time, and that tracing these ties will lead to revelations that also concern the present: the politics of memory, what we think we know, what we appreciate and safeguard, how we remember, how we forget, and how one imagines that which one hasn't witnessed.

The film that we are going to watch has been watched thousands of times by millions of people. I assume that more than half of us in this room today have seen it before at some point, willingly or accidentally. In the discussion that we will be able to have after the screening, it might be interesting to reflect on the expectations and memories with which you have come to see this film again, and what the re-encounter has meant to you.

I hope that I can start to explain a bit what this project, re-selected, is about by trying to answer a simple question: Why watch the film twice? We are going to watch Alain Resnais's Nuit et brouillard first in the French original version with the text by Jean Cayrol spoken by Michel Bouquet, with English subtitles, and then in the German version with the translation by Paul Celan spoken by Kurt Glass. You will also notice that while in the original version of the film several sequences are in color, on the German 16mm print the film is entirely black-and-white.[1]

Watching the same film twice – the fact of the "two versions" should already raise the question if it is actually the same film that we are going to watch twice. I do not want to be blunt by saying that the different languages make what we are going to see two entirely different films. However, with this film – like with many others – it is worth paying attention to how it has been translated into another language.[2] In this particular case of a film that traces and analyzes the mass extermination system implemented by Nazi Germany all over Europe, the German translation by Paul Celan inherited from Cayrol's original text theessential difficulty of having to break a silence. A silence that had been kept for reasons of shame, ignorance or denial, but that also had to do with the fact that many of those who had witnessed and survived the horrors of the concentration camps had found themselves unable to speak about them. Both Cayrol and Celan had been affected by Nazi prosecution and deportation – Cayrol as a member of the French Résistance, Celan as a Jew. Cayrol and Celan were prolific poets of their time, and their texts are dense and complex literary works based on personal experiences. Nuit et brouillard was in fact the second text by Cayrol that Celan translated into German: in 1954, just prior to working on the film, he had already translated Cayrol's novel “L'espace d'une nuit.”[3]

For Celan, translating Nuit et brouillard into German not only meant negotiating his own experience of the Nazi terror with Cayrol's, but it also required him to translate the words of a resistance fighter into the language of the perpetrators. This aspect of the task loomed large for Celan and it must have made it a painful challenge for him. Accepting the task was consistent however with his resolution to continue writing in German even after the worst had happened; to bring about in his poetry a language which was marked and haunted by the atrocities it had witnessed and served, and to actually change the German language for good.

The very title of the film is a hint to the fact that translation is much more than a technical procedure, that every translation simultaneously uncovers and affects the body of a language. “Nuit et brouillard” is the literal translation for the common name of a decree enacted by Adolf Hitler in December 1941: the so-called "Nacht-und-Nebel-Erlass", Night and Fog decree, provided the legal (if unlawful) base for the deportation of those who resisted German occupation in their countries of origin to be tried and sentenced by special courts on German or German-occupied territory. The decree explicitly aimed at making the victims disappear, if possible through a death penalty and its immediate execution, or through deportation without notification of relatives or legal institutions. Prisoners deported on the base of this decree were classified by the Nazi administration as NN, Nacht und Nebel, and the two letters would eventually also be stitched on their clothes, as can be seen in the film. By the end of the war, about 7,000 people had been victimized under this category. The Nacht-und-Nebel decree was dealt with during the Nuremberg Trials in 1947 and it was rated a Crime against Humanity.

The French film historian Sylvie Lindeperg suggests that the Nazi bureaucracy borrowed the expression Night and Fog from Richard Wagner's “Rheingold” libretto in which “Nacht und Nebel” is a magic formula to make someone invisible. However, the expression had an idiomatic meaning in German before, signifying that something happens unnoticed or in secret, when nobody is watching or under poor conditions of visibility. While for Germans, then, “Nacht und Nebel” had a common meaning before it was adopted for a particular form of deportation, the expression “nuit et brouillard” was new to the French language and exclusively referred to the experience of those who were deported and categorized NN. The cynicism of a picturesque term like “night and fog” being used to describe an instrument of terror became part of the experience of the victims. Some of them would later refer to the word-play in their writings, among them journalist Odette Améry in her memoirs of deportation to Ravensbrück and Mauthausen, and Jean Cayrol himself whose first volume of poetry published after the war, in 1946, was titled “Poèmes de la nuit et du brouillard” (Poems from Night and Fog). It comprised poems he had written during his imprisonment in Gusen and Mauthausen. When in the summer of 1956, the expression “Nacht und Nebel” returned to the German language in Celan's translation of the film, its idiomatic function had forever changed, because it carried with it this history of violence and occupation. Those who didn't know, would now learn.

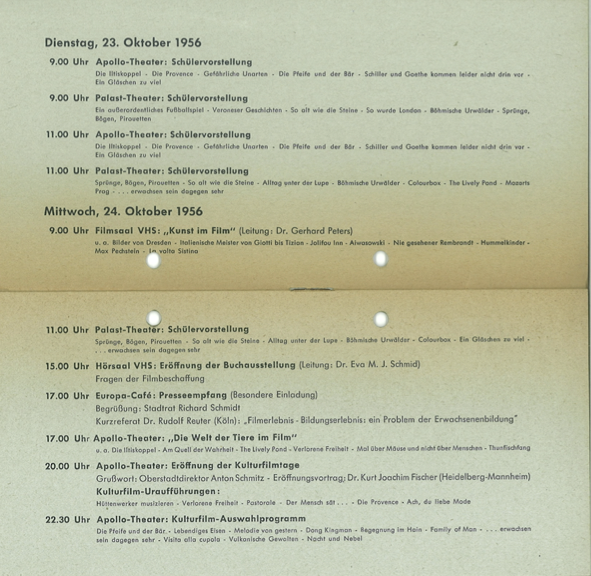

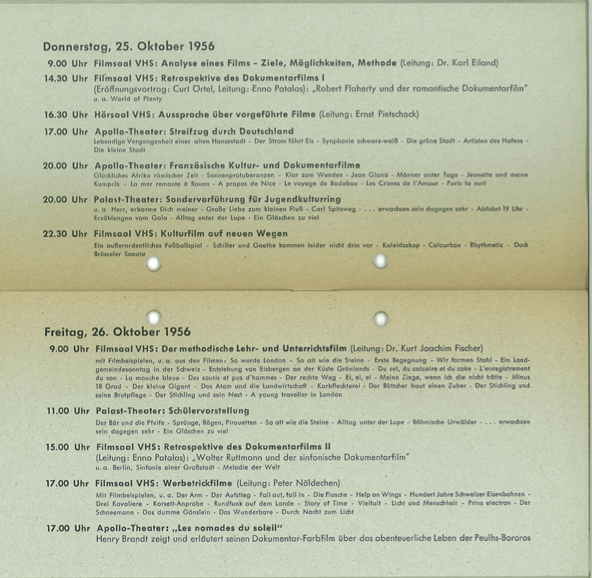

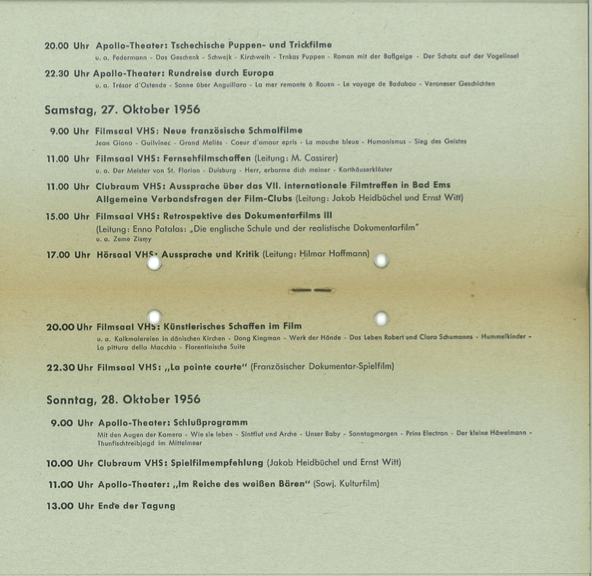

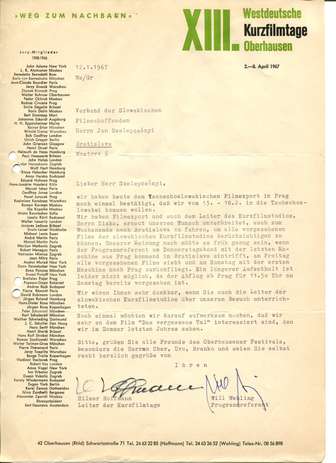

Nuit et brouillard was screened at the 3rd edition of the “Westdeutsche Kulturfilmtage Oberhausen” and it was among the eight films which the jury honored as “particularly remarkable.”[4] Night and Fog was screened once, on 24th October and it was part of a compilation program of ten films beginning at 10.30 pm at the Apollo theater. Night and Fog was the last film in the program, preceded by a 20th Century Fox documentary titled Volcanic Violence (German: Vulkanische Gewalten). This means that Night and Fog probably did not start before 11.30 pm or even midnight, which makes me wonder how many people actually saw the film on that day here in Oberhausen.

As is well known, the film's world premiere at the festival in Cannes, a few weeks earlier, had caused a scandal because the festival had buckled to an intervention by the German ambassador to not screen the film in competition arguing that it did not “serve the understanding between nations” (“dass er nicht der Völkerverständigung diene”), which was a common lever to suppress a film for the uncomfortable facts it made public. One result of the affair was that the West German government, in order to make up for the embarrassment the scandal had caused, quickly decided to acquire the film for a wide non-commercial distribution in schools and public institutions. Thus, after being the first country to oppose Nuit et brouillard, West Germany became the first country in which it was widely seen. As early as December 1956, the West German language version was finished and the German Federal Press Office ordered 200 prints for its political education program. For budget reasons, these prints were 16mm black-and-white and it is a reprint of these which we are going to see in the second half of today's program. At the very end the print contains a short trailer of the “Landeszentrale für politische Bildung,” the Federal Bureau for Political Education, which we will get to see, if the projectionist lets us. In this form, Night and Fog became a common element in the curriculum of West German schools, on the program of film clubs and the political education of labor unions, cultural associations and churches.

I haven't been able yet to verify in which form the film was screened in Oberhausen in October 1956. This German version did not exist yet, but we can assume that a German translation of Jean Cayrol's text had been produced by the festival and that the German text was read over loudspeakers during the projection. In fact, when the film was screened again at this festival in 1966 in a retrospective curated by Enno Patalas, the catalog featured an excerpt from the German commentary. This excerpt is not identical with Celan's text and was probably quoted from the German dialogue list produced in 1956, which would still have existed in 1966 but appears to be lost now.

So why watch Night and Fog twice? Why watch it again in the first place? The idea first suggested itself by the fact that prints of these two versions exist in the archive of this festival. (They are of course not the only versions that exist of the film; there even exist two more German versions produced in East Germany in 1957, respectively in 1977, whose commentary differs distinctly from Celan's. These will probably become a topic of this project, too, at some point, as their genesis can serve as a prism through which to explore the different politics and aesthetics of remembrance in East and West Germany.)[5] At the core of the re-selected project lies the idea that revisiting films from the past can be a rewarding experience in the present. That the history not only of each film but of each print is rhizomatically connected with and entangled in the histories of its time, and that tracing these ties will in the end lead to revelations that also concern the present: the politics of memory, what we think we know, what we appreciate and safeguard, how we remember and how we forget, and how one imagines that which one hasn't witnessed – bearing in mind and holding dear an important idea of Walter Benjamin's, noted in "The Task of the Translator," that one can "speak of an unforgettable life or moment even if all men had forgotten them." (Benjamin 1972, 10; quoted and translated from the German text)

Why the same film twice? As an archive project, re-selected is also in favor of the second look, even a third look, of a practice of repetition, rewinding, watching again and again, in an attempt to understand better, to see more clearly. At its core, this project is about recognizing and appreciating differences, befriending the idea that films lead a very heterogeneous existence that cannot easily be homogenized to the concept of a one and only original. How can we ignore the different ways in which a film has met its audiences over the years? How can what we say about a film in history be said independently from its unfathomable existence in the memory of those who saw it, especially if they saw it in different versions? How can we really expect to see the same film twice?

One of the many who were marked by watching Nuit et Brouillard in school was French film critic Serge Daney. In his famous essay, “The Tracking Shot in Kapo,” he recalls how he was exposed to the film regularly when his literature teacher at the lycée Voltaire, Henri Agel, in order to spare himself and his students the burden of Latin lessons, turned the classroom into a cine-club:

Out of sadism and probably because he had the prints, Agel showed little films designed to seriously open the students' eyes: Franju's Le sang des bêtes and in particular Resnais's Nuit et brouillard. Through cinema I learned that the human condition and industrial butchery were not incompatible and that the worst had just happened. (Daney 2007, 19)

In what was to become his last text on cinema, a long conversation with his friend and colleague Serge Toubiana that took place in February 1992 in a hotel in Aix-en-Provence and that was published under the title "Perséverance" in 1994, Daney calls Nuit et brouillard "the film that marked me." (Daney 2007, 90) At this point in their conversation the film prompts an interesting remark about cinema as such. Daney says,

cinema can only bring back what has already been seen before: well seen, poorly seen, unseen. Ten years later Nuit et brouillard brings back what wasn't seen, bearing in mind that the images of the camps filmed by George Stevens, or those assembled by Hitchcock, have been stashed away by the Americans and the British. (Daney 2007, 90)

Here is an idea that I find very important for this project re-selected, the idea that even when we see something in a film for the first time, we know that it had been seen before, that it was visible, even if only for a few, even if it was hidden, and even if too many people have tried very hard not to see it. And this is true for the things that Daney saw for the first time when watching Nuit et Brouillard. He says it: "Ten years later Nuit et Brouillard returns what wasn't seen," pointing out that the images that were shot during the liberation of the concentration camps by American and British camera men had quickly been locked away as an early concession to Cold War politics.

When Daney says that the raison d'être not only of this film, but of cinema as such was to bring back what had already been seen before, he seems to be referring to the archival function of cinema, to the fact that films, whether fictional or documentary, always create a record of their times, of something that existed and of the ways in which it existed. I think however, that this was not the primary intention of what he said. For Daney, Nuit et Brouillard was the revelation that cinema could only bring back what had been seen before – not only because it brought back images of what was already in the process of being forgotten, but also because the film helped him to understand the absence of his own father, whom he never knew, probably because he had been deported and murdered by the Germans before Daney was born. When seeing Nuit et brouillard for the first time, Daney did not expect to see his father in the images, but the film revealed to him the fact that someone had seen him, that what had happened to his father had been visible. For me, the essence of Daney's thought is that seeing something in the cinema brings us in touch with what is visible and through it with the possible gaze of others, with the fact that not only has what we see been seen before, but also that we are usually not alone in seeing it again now. Watching a film, even if we watch it alone and in private, is always a shared experience, an experience that engages us with others who are often far away or not there anymore. And one of the questions re-selected can be understood to ask is, who they are.

Let me quote Serge Daney's thought once again: "Cinema can only bring back what has already been seen before: well seen, badly seen, unseen." The possibilities opened up by "well seen, badly seen, unseen" suggest that a certain repetition or revisiting, for example when watching a film again, is not merely a thing for cinema nerds and film researchers, but that when watching a film again we are doing something that touches the core of what cinema is: the possibility to see again what has been seen before, to reflect on its earlier audiences, and to experience the same thing different; to realize that while we think we are watching the same film again, it is actually us who have changed. The context is different and the same film appears to us in a new light, a light that is filtered through layers of time that have settled on it (and on us) like sediment.

In a short note on memory titled "Ausgraben und Erinnern" ("Excavation and Memory"), Walter Benjamin suggests that history is never written once and for all, and that in order to find something out about the past, one "must not be afraid to return again and again to the same matter." (Benjamin 1972, 400; quoted and translated from the German text). I hope that this project, by recognizing that a film comes to an audience as a "copy", and that each screening of it is engaging us with a repetition of something that will however never be the same thing twice, will help to bring about a more nuanced understanding of the practice of cinema and that it will also create fruitful, revealing and engaging encounters with ourselves, with others, with films that – as Daney also says somewhere – are watching us every time we are watching them.

I thank the staff of this festival for making these screenings, this re-visiting possible.

This text is also published in the book, Accidental Archivism. Shaping Cinema’s Futures with Remnants of the Past (meson press, 2023), edited by Vinzenz Hediger and Stefanie Schulte Strathaus.

References

Améry, Odette 1945. Nuit et brouillard. Paris: Berger-Levrault.

Benjamin, Walter 1972 (c.1932). “Ausgraben und Erinnern.” In Walter Benjamin: Gesammelte Schriften, Vol. IV.1. Frankfurt/Main: Suhrkamp.

Benjamin, Walter 1972 (1923). “Die Aufgabe des Übersetzers.” In Walter Benjamin: Gesammelte Schriften, Vol. IV.1. Frankfurt/Main: Suhrkamp.

Cayrol, Jean 1946. Poèmes de la Nuit et du Brouillard. Paris: Seuil.

Cayrol, Jean 1954. L'espace d'une nuit. Paris: Seuil.

Daney, Serge 2007 (1994). Postcards from the cinema. Oxford/New York: Berg.

Lindeperg, Sylvie 2007. Nuit et Brouillard. Un film dans l’histoire. Paris: Éditions Odile Jacob.

van de Knaap, Ewout 2008. Nacht und Nebel: Gedächtnis des Holocaust und internationale Wirkungsgeschichte. Göttingen: Wallstein.

Footnotes

[1] The French version screened was the digitally restored version, provided on DCP by Tamasa Distribution under license from Argos Films. The German version was a worn black-and-white 16mm print from the archive of the International Short Film Festival Oberhausen. A 35mm print of the French version is also kept at the festival archive, but has turned entirely red.

[2] Primary sources for information on the production and reception history of the film are Sylvie Lindeperg´s Nuit et brouillard, Un film dans l'histoire, published in French in 2007 and in a slightly extended German version in 2010, as well as Ewout van de Knaap´s Nacht und Nebel: Gedächtnis des Holocaust und internationale Wirkungsgeschichte from 2008; see references at the end of the text.

[3] Published in German as “Im Bereich einer Nacht,” in English as “All in a Night.”

[4] At the time, there were no competition programs in Oberhausen yet and no awards were given.

[5] Since then, two comparative screenings of the East and West German versions of Night and Fog took place, one as part of the re-selected project in collaboration with Mareike Bernien and Nicole Wolf in May 2019 in the context of the first “The Whole Life” congress at the Lipsiusbau in Dresden; another in 2021, together with Jörg Frieß at the Documentary Film Festival in Leipzig within the retrospective, “Die Juden der Anderen” (“The Jews of the Others”), curated by Ralph Eue. A comparative screening of the French and the Dutch versions of the film took place at the Brussels Cinematek in January 2019 as a re-selected project presentation. These screenings were occasions to discuss how each version of the film had its distinct history of reception and to what extent the circumstances under which these different versions have been archived and are still accessible are also quite different. The discussion after the screening in Brussels concerned the fact that the two languages, French and Dutch, represent an ongoing dichotomy within Belgian society, the quite different ways in which the years under German occupation have been commemorated in these respective communities, and how questions of collaboration and complicity in the deportation system have been dealt with by post-war generations. Likewise, the comparative screenings of the two German versions provided the ground for a debate on the stark differences in East and West German “commemoration culture” (Erinnerungskultur) in relation to the Nazi period and the Shoah. They also made overtly visible how the wholesale delegitimizing of the GDR and its institutions after reunification has affected archival policies: while the West German version of Night and Fog with the translation by Paul Celan is readily available from various digital and analogue sources, the DEFA version of the film has only been preserved at the Federal Film Archive (Bundesarchiv-Filmarchiv) as what is reported to be a “unique 35mm archive print”. This print was not available for the screening in Dresden in 2019; the only form in which the archive would make this version of the film accessible to us was a digital file made from a time-coded VHS tape. The squalid impression thus brought to the screen could be seen as symptomatic for the devaluation of specifically East German perspectives on history and was commented as such during the discussion. Thanks to additional efforts by Ralph Eue, the Federal Archive made the 35mm print available for the screening in Leipzig in 2021. The screening experience was entirely different and in the ensuing discussion archival politics played a less important role than the differences in tone and vocabulary between the two versions and how they reflect the different “readings” of the fascist era in East and West Germany in the 1950s.

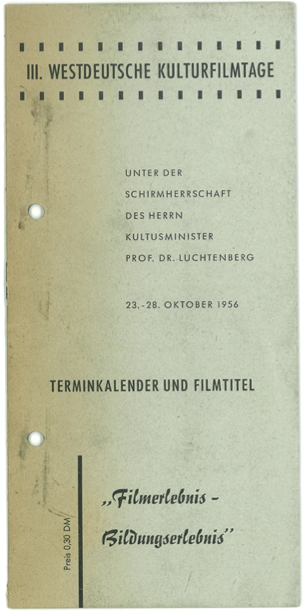

Nuit et Brouillard in Oberhausen 1956

The screening of Nuit et Brouillard (Night and Fog) at the "3rd West German Cultural Film Days" in Oberhausen on 24 October 1956 was probably the third public screening of the film in Germany. It had previously been shown in June in a special screening at the Berlin International Film Festival and in early October at the annual meeting of film clubs in Bad Ems. However, it wasn't until December 1956 that the German language version known today, based on the translation by Paul Celan, was available; so Berlin, Bad Ems and Oberhausen probably had to make do with their own translations. In Oberhausen, the German text was presumably read over an auditorium loudspeaker.

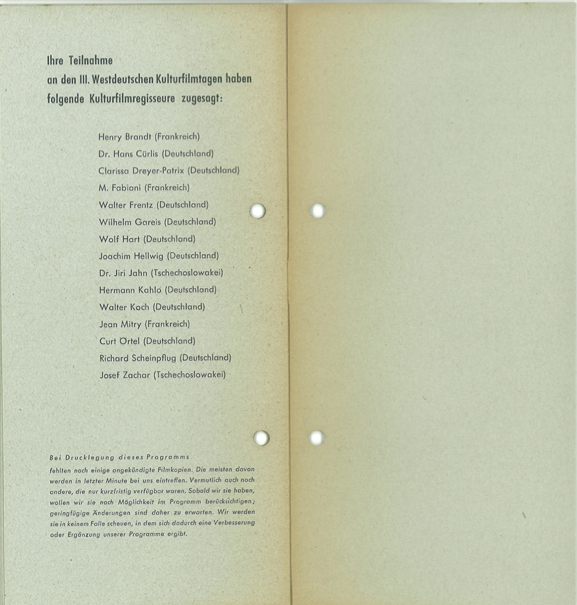

At that time, the "West German Cultural Film Days" still had the character of a conference. They were held under the auspices of the Oberhausen Adult Education Centre and had the motto "Film Experience is Educational Experience". They were aimed primarily at teachers, journalists, representatives of local authorities and educational and cultural institutions as well as other facilitators who were meant to take short film seriously as a medium for educational work.

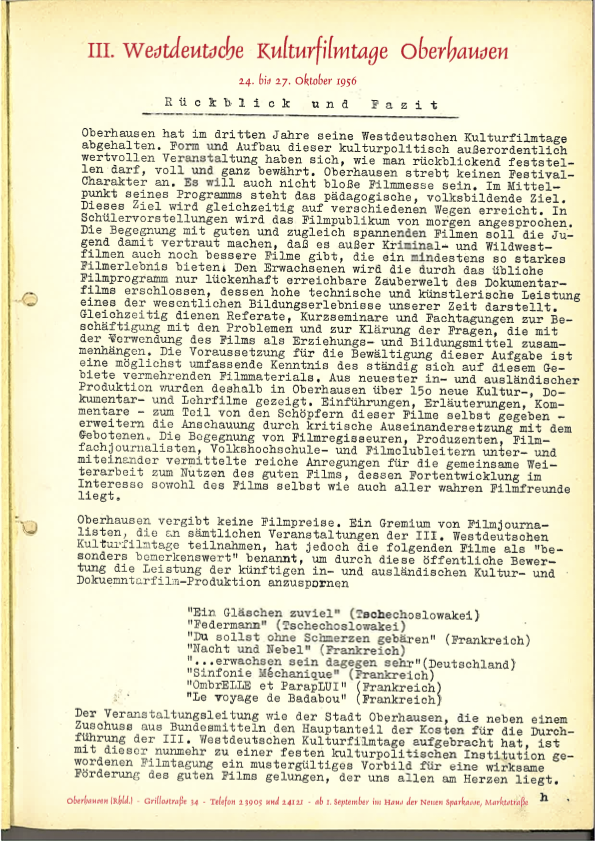

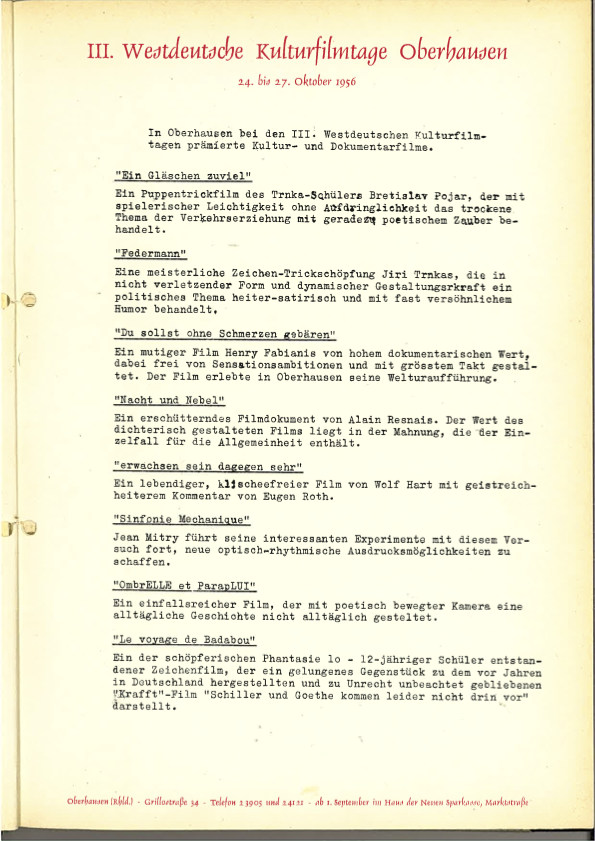

In the final report of the 3rd West German Cultural Film Festival, this focus is unequivocally stated (see here for the original German text):

"Oberhausen does not aspire to festival character. Nor does it want to be a mere film fair. Its programme is centered around pedagogical goals, the education of the people. These goals are achieved simultaneously in various ways. The film audience of tomorrow is reached in school screenings. The encounter with good and at the same time exciting films is intended to familiarise young people with the fact that, apart from crime and wild west films, there are also better films that offer at least as powerful a film experience. Adults are introduced to the magical world of documentary film, which is only partially accessible through the usual film programmes and whose high technical and artistic achievement represents one of the essential educational experiences of our time. At the same time, lectures, short seminars and specialist conferences serve to deal with the problems and clarify the questions connected with the use of film as a means of education."

No prizes were awarded in Oberhausen in 1956 (although this changed in the next edition). However, at the end of the event, a panel of film journalists gave official recognition as "particularly noteworthy" to a selection of eight films. Among these was Night and Fog. In the final report, the film is described only as a "harrowing film document". "The value of the poetically crafted film lies in the admonition that the individual case contains for the general public." There is no concrete reference to the content of the film, the key word "concentration camp" is not mentioned.

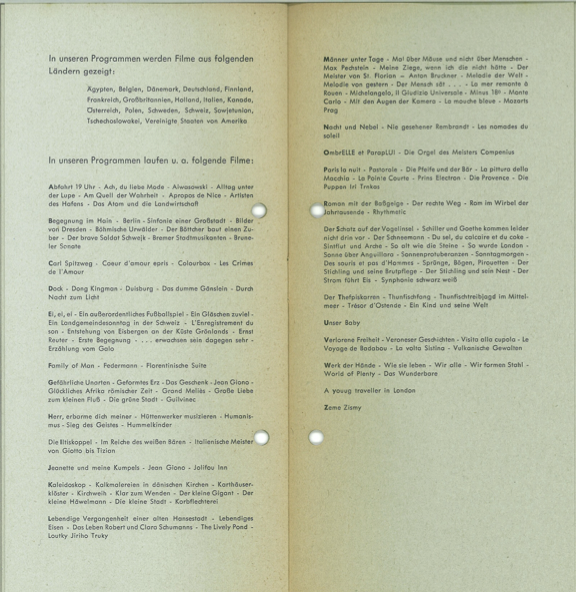

Night and Fog was shown on 24 October in a programme announced as a "cultural film selection" that started at 10.30 pm and included ten films in total. Night and Fog apparently ran as the last film in the programme and may not have started until after midnight (see here for the 1956 programme flyer).

Since the Short Film Festival archives have only sparse documents on the 1956 programme, and the films were usually announced only in German, it is no longer possible to identify all the films in this programme without a doubt. It will have been approximately this sequence of films:

[The Pipe and the Bear]

probably: Trupka i Medwed, USSR 1955, Director: Alexander Ivanov, 10 min

Animation

[Living Iron]

probably: Living Iron, GDR 1955, Director: Berthold Beißert, 16 min

Portrait of the art blacksmith and GDR national prize winner, Fritz Kühn.

[Melody of Yesterday]

Director: Walter Koch, FRG 1956, 12 min

Dong Kingman

Director: James Wong Howe, USA 1954, 15 min

Portrait of a contemporary painter in Chinatown, NYC.

[Encounter in the Grove]

Director: Th. N. Blomberg, Caspar van den Berg, FRG 1955, 14 min

Family of Man

Not clearly identified. Possibly a documentary about Edward Steichen's exhibition project of the same name at the Museum of Modern Art, NYC, 1955.

[... being grown up, on the other hand, very much]

Director: Wolf Hart, D 1956, 13 min

Visita alla cupola

Not identified.

[Volcanic forces]

possibly: Volcanic Violence, USA 1955, a Movietone production about volcanoes in Hawaii.

Night and Fog

Nuit et Brouillard, Director: Alain Resnais, France 1956, 32 min

Documents

Programme flyer Oberhausen 1956

Review and Conclusion 1956

Three German Versions

The reception history of Night and Fog was very different in West and East Germany. The Federal government tried to make up for the diplomatic embarrassment caused by the West German intervention against the screening of the film in Cannes 1956 by having a German version of Night and Fog produced as early as autumn 1956 and making a large number of 16mm prints available for political education work and non-commercial distribution. For cost reasons, however, this version was entirely in black and white, whereas in the original version the parts shot in the present are significantly in colour. This version with the German text by Paul Celan has become canonical in Germany.

The fact that the DEFA (state film production of the GDR) had an alternative version with a new translation produced in 1960 was hardly known for a long time, as it was ultimately not released in cinemas as planned, but was only used in film clubs and in educational work. The prehistory and creation of this version are described in detail in the relevant studies by Sylvie Lindeperg (2007) and Ewout van de Knaap (2008).

For the television cycle "Filme contra Faschismus" (Films against Fascism), a new version was produced once again, presumably in 1978, by GDR television, but its commentary now differed greatly from the original and was also never authorised by the production company Argos.

It is worth comparing the three German text versions, especially against the background of very different memorial cultures in the two German states. The transcriptions were kindly provided by Mareike Bernien and Sylvia Görke. Many thanks for this precious work.

Imprint

re-selected Dossier #3

Night and Fog – Re-Encounters with a Film

Editing, texts: Tobias Hering

Coordination: Katharina Schröder

Implementation: Louisa Schön

Documents from the archive of the International Short Film Festival Oberhausen.

Film still from Night and Fog courtesy of Argos Films.

Thanks to: Argos Films, Mareike Bernien, Ralph Eue, Jörg Frieß, Sylvia Görke, Nicole Wolf.

Published by

International Short Film Festival Oberhausen

Grillostr. 34

46045 Oberhausen

Deutschland

© 2023

©

©#2

Northern Lights

Oberhausen´s erratic relations to Sweden in the 1960s and 70s.

The International Short Film Festival's relations with the social democratic "model country" Sweden got off to a surprisingly bumpy start in the 1960s. A dispute over the rejection of the film Ferrum (1963) led to a four-year silence between the Short Film Festival and Svenska Filminstitutet, which for a long time operated in a centralist manner. Forced to seek direct contact with filmmakers and independent distributors such as FilmCentrum, the Short Film Festival built up an informal network in which, in addition to various journalists, German documentary filmmaker Peter Nestler, who had emigrated to Sweden in 1967, played a central role. Yet, with Nestler too, the Short Film Festival was linked by a by no means smooth history... re-selected Dossier No. 2 recapitulates an eventful period in which the stakes were high, in festival policies as much as in politics at large.

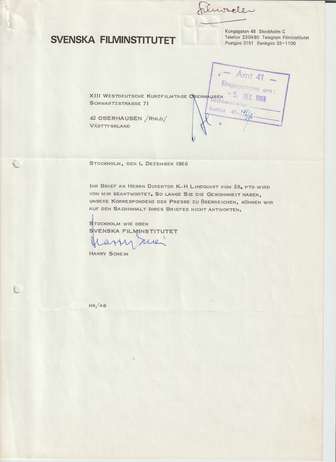

Stuck on Ferrum

Oberhausen's relations with the Swedish Film Institute 1963-1969.

by John Sundholm

The proceedings caused by the rejection of the short film Ferrum (Gunnar Höglund, 1963) by the Oberhausen Short Film Festival in 1963 constitute a case in point for uncovering the film-political situation in Sweden at the time by shedding a light on both its international aspirations and national lines of conflict. Significantly, the rejection provided the Swedish Film Institute (SFI) with a pretext to turn the Oberhausen festival into a scapegoat in the face of increasing dissent and dissatisfaction with the new Swedish film policy. After Oberhausen had rejected Ferrum, the SFI would boycott the festival for six consecutive years, thereby wilfully jeopardising international prospects for Swedish short films during a period of significant change and reorientation.

Letters and documents in the festival archives in Oberhausen reveal not only the arrogance of SFI but also the amount of labour necessary to mount an annual international film festival in a time when the material culture of film was analogue. If today, “sending” films is typically a matter of server capacities and file formatting, in the pre-digital era making a film available for distant audiences required a number of physical practices and logistic procedures. More often than not, this was a time-consuming and painstaking affair, especially when substandard or minor film production such as short films was concerned.

This widely neglected material history of film and film festivals is important for many reasons. We are nowadays offered an immense amount of digital audiovisual representations from the past, and thus the illusion of having access to the past, while the conditions under which films were historically produced and distributed are disregarded. The digital promise of easy access obscures the material histories of films; that they were physical objects that travelled or that demanded one to travel; that film was a delicate and vulnerable object, “critical” in more than one sense, handled by shippers and porters, by customs officers, governmental authorities and projectionists: physical procedures which caused material inscriptions and other traces in institutional archives, on the film cans and the actual film material itself.

When fathoming the effects which material practices around the distribution and exhibition of films had on history and historiography, the Oberhausen film festival has an interesting past to revisit. What adds to the exclusivity of Oberhausen is that being dedicated to short films, the festival operated within a form of film that was typically said to grant greater artistic freedom than feature film production. The genre also provided Oberhausen with a particular mission as a window for filmmakers from the Eastern Bloc whose films were often made to play intricate roles in Cold War soft diplomacy. Even in a presumed model country like Sweden, the materiality of film allowed decision makers and gatekeepers to exert influence and execute control over the circulation of film reels. The material conditions – both financial and physical – of analogue film created both the desire and the possibility to exert control, and thus film was controlled.

The Swedish Film Institute (SFI) was founded in 1963. It was created as a foundation headed by Austrian-born Harry Schein and with the mission to both secure a future for the national film industry and to enable the making of films that primarily served other interests than that of the industry.

Schein had arrived in Sweden as a Jewish refugee from Vienna in 1939, when he was fourteen years old. Twenty years later he had made a successful living and become a well-off member of society with diverse cultural interests and close ties to the leadership of the Social-Democratic party that ruled the country. Schein succeeded in making SFI into the institute, which means it would not only become the key institution for allocating funds for feature film production; the institute also founded the first film school in Sweden, established the national film archive and took over Sweden’s leading film journal, Chaplin. Schein’s design of SFI gave him full control and he did not hesitate to use his power. Schein’s public image was additionally fostered by his marriage to one of the most prominent Swedish actors of the time, Ingrid Thulin, possibly best-known through her appearances in Ingmar Bergman’s films of the 1960s. The personal success story of Harry Schein reflected the international image of Sweden as a culturally and financially prosperous country. An image that was not challenged by the actual decline of the Swedish film industry because the international attention was turned towards the Swedish art-house cinema. Sweden was considered as one of the European exponents of the rising art-house cinema of the 1960s.

Given such a constellation for Swedish film culture, it is no surprise that short film production would become a dilemma for the newly founded film institute. Short film culture was marginal, always an exception, and it would re-appear time and again as the film form that threw a spanner in the works of SFI’s film policy. While for someone like Schein short film was certainly a minor and therefore inferior form of production, it was precisely its marginal status that eventually made it precious for the individual filmmakers. The “minor” promised full freedom, whereas if you worked within the regular feature film business (industry or art-house), external control was a natural and accepted part of the production culture. It came as a disappointing surprise for many filmmakers that the very institute that had been founded to foster film culture did not engage in the form that was considered the most diverse and free within the otherwise tightly kept film production. After all, even such heavy industries as mining companies were giving free hand to the directors of their commissioned PR films.

From the perspective of a new and aspiring institution like SFI – that held great local power – the Oberhausen short film festival was considered a minor player. Previously, short film production in Sweden had predominantly taken place under the auspices of governmental agencies, NGOs and the industry. The latter both in the sense of industrial companies financing films within their PR budget, and the established film industry producing short films. This was the case until the great transition within Swedish film culture and film policy in 1963, that is, until the founding of SFI as a national, public body for funding film production.

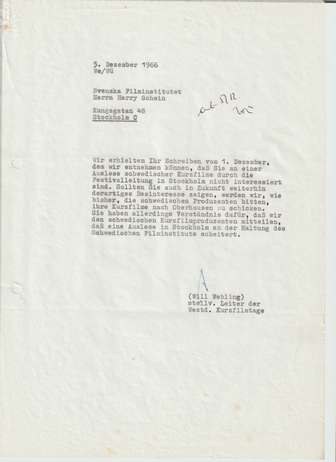

The film Ferrum, which was to become an apple of discord, had been commissioned by the Swedish mining company LKAB and was produced by Nordisk Tonefilm, which – according to what Schein would claim retrospectively[1] – had submitted it for the 1963 Oberhausen Short Film Festival. The festival rejected it.[2] Schein resubmitted it the next year, and when Oberhausen rejected it again he appeared to be scandalised. While Schein claimed that the film was excellent, and that, if SFI was invited to submit films to the festival, these should be accepted, Swedish film critics would later claim that Oberhausen had informed Schein that Ferrum had already been submitted and rejected in the previous year and that due to its participation in many festivals during 1963, there was no way for them to accept the film for their 1964 edition.[3] According to the Swedish press the SFI's (Schein's) final reply was that “the institute can not be expected to submit bad films just because a festival organisation has bad taste.”[4]

Ferrum was an object of great national pride in Sweden. It had received many awards, its director, Gunnar Höglund, was highly appreciated, and the music was composed by the young avant-garde composer and musician Karl-Erik Welin. When submitting the project in 1960, Höglund had wanted the music to be composed by the internationally renowned composer, Karl-Birger Blomdahl, a leading cultural figure at the time in Sweden. When pitching the colour film in 35 mm to the mining company LKAB, Höglund explained that “sound effects and music should form a musical unit, an ore symphony visualised. Once implemented, this should make the conventional narrative speaker redundant. Therefore, there is no voice-over. Synthesis – iron as an idea – may come closer to us that way.”[5]

From today’s perspective, the film is an intriguing example of how heavy industry is romanticised into an audiovisual harmony that is in the service of eternal societal (and social-democratic) development and progress. Mining and music, iron and image in perfect harmony.

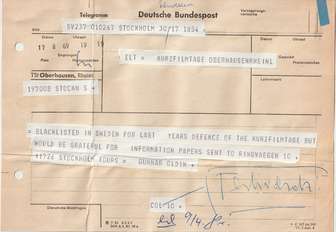

It is easy to see how Ferrum satisfied what Schein would consider the rationale for short film production as well as his ideals for short film aesthetics. However, my objective is not to speculate on underlying motives and aims, but to point out the conditions and histories behind SFI’s boycott of Oberhausen and their consequences for the film festival. Correspondences in the Oberhausen archive show that Schein could not forgive the festival organisation for having “leaked” part of their previous exchange to the press, as Schein would put it. It was in fact Gunnar Oldin, Swedish film critic for both press and television and one of Oberhausen’s Swedish contacts at the time, who had been informed about the correspondence between Oberhausen and SFI. Oldin was upset about Schein’s behaviour and wrote about it, criticising the SFI for its refusal to collaborate with Oberhausen.[6]

Oldin’s coverage of this affair was an early warning for the coming long-term debate in Sweden concerning Harry Schein’s dominating position in Swedish film politics, but also his sceptical attitude towards short film production. The debate would escalate and receive new dimensions when the Swedish co-op FilmCentrum was founded in 1968, inspired by the American Canyon Cinema and Filmmakers’ Co-op in New York. FilmCentrum would soon, like so many like-minded cooperatives all over Europe, develop into a site for politically oriented and politically activist filmmaking and distribution.

This local conflict around film policy put Oberhausen in a difficult position. The festival wanted access to as many Swedish short films as possible and the SFI was not only the natural partner to ask for organising the screenings for the selection committee; as a national institute it was also expected to suggest potentially interesting films to be considered. In 1966, when Schein and the SFI again refused to collaborate, Oberhausen made an effort to establish direct relations with Swedish filmmakers. Letters were sent to well-known figures like Peter Weiss, to people from the industry, and to experimentalists like Åke Karlung and Hans Nordenström, the latter a long-term collaborator of the rising star curator and museum director, Pontus Hultén. An indication of the desperate urgency of these attempts is that at a closer look some of the measures taken seem oddly out of place: Peter Weiss, for instance, did have an early and promising start as a filmmaker in the late 1950s (and most of his films had been shown in Oberhausen). Yet, by the time Oberhausen asked him for advice in 1966, his last film, Hägringen (1960), was already dating back six years and he had switched to become an internationally acclaimed writer and playwright in the meantime. Also, when trying to get in touch with Hans Nordenström, the Oberhausen festival organisers first mistakenly contacted a namesake who was an official at the Church of Sweden.

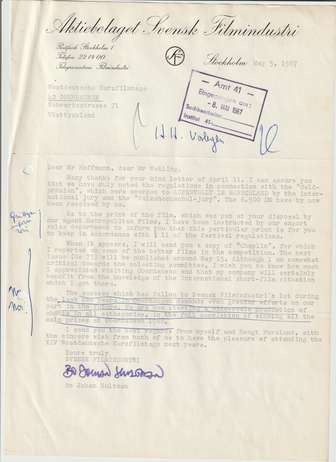

If Oberhausen was a marginal phenomenon for SFI, and thus not really worth any diplomatic efforts, Sweden was not a top priority for Oberhausen either. Eastern European short film was booming in the 1960s – and played a dominant role in Oberhausen – and the American experimental film movements had begun to catch attention as well. However, when Jan Troell picked up a first prize in Oberhausen in 1967 for his film Uppehåll i myrlandet (1965), the unresolved issue with SFI came up again. New efforts were made to receive substantial numbers of Swedish submissions, this time by asking critics and producers to recommend films and filmmakers for the festival. Among the producers who were approached was Bengt Forslund, who was not only a producer at Svensk Filmindustri but had co-written Uppehåll i myrlandet with Troell and had also been the film's production and unit manager. In his response to Oberhausen, Forslund mentioned the recently inaugurated SFI film school where, he said, several interesting short films had recently been made.

Forslund’s reply put the SFI’s boycott back on the agenda, since the institute was holding the rights to the films produced at the school. For Harry Schein the idea that Oberhausen could become a window for the Institute’s new film school was a pleasant prospect. The school had been one of his favourite projects within SFI, and acknowledgement by a festival like Oberhausen would support Schein’s claim on the home front that SFI actually did support short film production with significant financial aid. In short, while for Oberhausen it became evident that one just could not ignore the SFI when looking for access to a reasonably representative number of Swedish short films, Schein had his own reasons to welcome more cooperative relations with the Oberhausen festival.

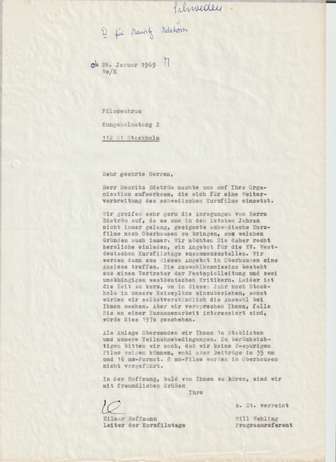

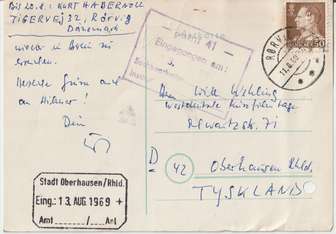

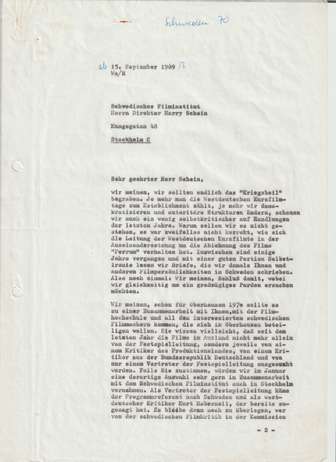

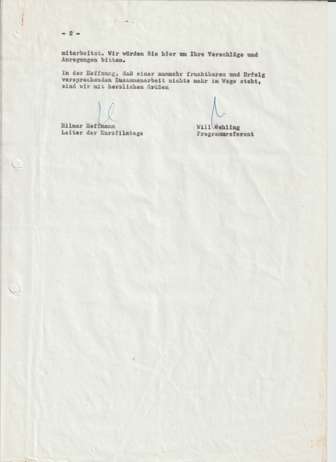

In August 1969 the festival management – director Hilmar Hoffmann and program coordinator Will Wehling – followed the advice by film critic Kurt Habernoll, who was designated to advise them on the Swedish selection, that a “proud gentleman” like Schein should be susceptible to some apologetic phrasing and that one should send him a “nice letter”. The nice letter was sent a month later. Hoffmann and Wehling announce therein that it was time “to bury the hatchet”, they admit to having made wrong decisions in the past and specifically apologise for the handling of Ferrum. In the name of future collaboration they ask Schein for pardon and suggest that the SFI organise selection screenings for the 1970 festival in Stockholm in January. Schein replies immediately, accepts their apology, suggests that films from the SFI film school should be included and that as part of a national award program, the SFI has already pre-selected the best Swedish short films of that year. These would be screened for the selection committee when visiting Stockholm.

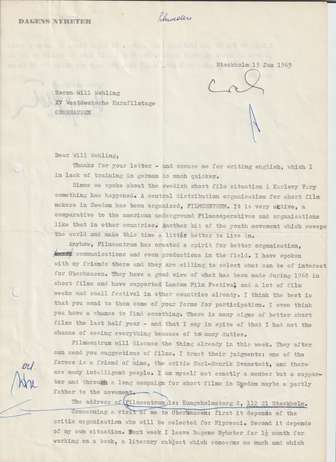

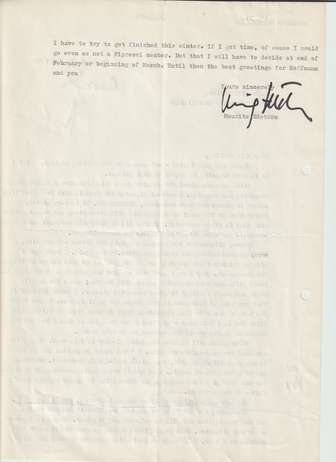

This correspondence and negotiation eventually led to a compromise but what is most interesting in Hoffmann and Wehling’s approach is that they are so conscious of who they are dealing with. Soon after the peace agreement with Schein they send a letter to Mauritz Edström, a leading film critic at the Swedish newspaper Dagens Nyheter, with whom they had been in contact throughout the 1960s. Hoffmann and Wehling are concerned that they might not get to see all Swedish short films that are of interest, if Schein and the SFI were to exclusively decide what would be shown to them. In the same correspondence they inquire about FilmCentrum which Edström had recommended to them in a previous letter.

However, it is impossible to distinguish any direct causal relations between Oberhausen’s and SFI’s agendas concerning the films that actually were chosen for the festival during the years of the controversy. The past is more messy and complicated than that, encompassing a vast ensemble of people, institutions, interests and commitments. Many filmmakers chose to contact Oberhausen directly, either encouraged by film critics or producers, or out of their own initiative. Some of the most original filmmakers of the time did submit work or contact Oberhausen but were not accepted. One example was Bo Jonsson, one of the first students at SFIs film school; another was the amateur film-maker and full-time industrial worker, Sven Elfström, Sweden’s most politically outspoken experimental filmmaker.

Thus, although SFI`s refusal to collaborate did not imply that Swedish films were completely blocked from entering the festival. Rather, Ferrum was like a McGuffin – the Hitchcockian device that sets a narrative in motion – whereas the controversy as such is an example of the material conditions of film as an absent cause in film culture. A film that happens to appear at a festival and is being enjoyed in the theatre – while its material base is transformed into light and sound that appears on the screen as if this was its true nature – reveals nothing about its preceding procedures, institutional logistics and conditions of production. Ferrum, of course, did not ever make it to the screen in Oberhausen, but left a distinct trace in the archive that reveals some of the crucial conditions for short film culture at the time. Embodying such material histories, the collection of letters and other written documents in the festival archive in Oberhausen provides us with a glimpse of the social whole of film culture.

Filmography:

Watch Ferrum here

Watch Uppehåll i myrlandet here

Fußnoten

[1] Harry Schein: ”Kortfilmsmytologi”, Dagens Nyheter 9 Jan. 1965

[2] No record of this decision could be found.

[3] Mauritz Edström ”DN-kortfilm tävlar i Oberhausen-festivalen”, Dagens Nyheter 5 Febr. 1965.

[4] Ibid.

[5] ”Ferrum. Kortfilmsförslag för LKAB av Gunnar Höglund”, 1960. Script at the Library of the Swedish Filminstitute.

[6] Edström 1965.

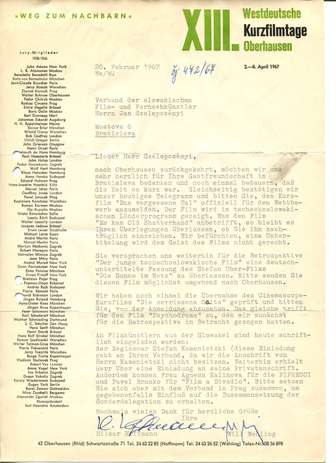

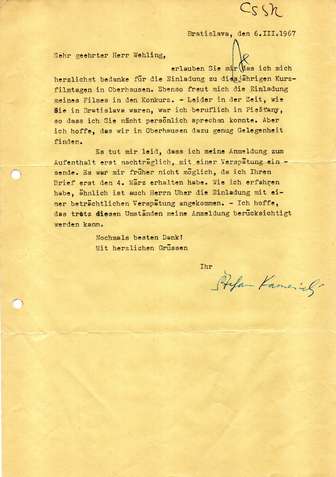

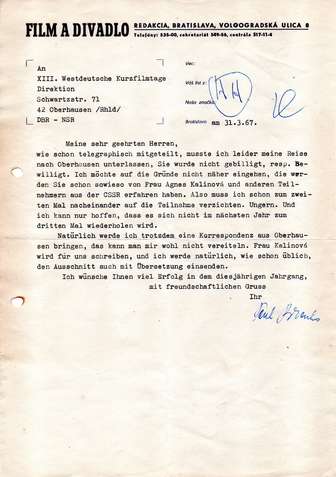

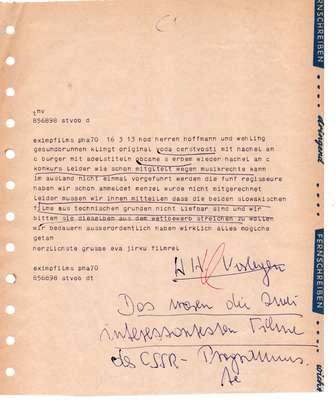

Documents for "Stuck on Ferrum" (1965-1970)

Peter Nestler and the Oberhausen Festival

by Tobias Hering

The following chronicle traces the intricate and contradictory history that connects the Oberhausen Short Film Festival with documentary filmmaker Peter Nestler. It is based largely on research in the Festival's documents archive and makes no claim to completeness. Unless otherwise noted, the documents cited are correspondences filed under "Sweden", in an archive arranged by festival year and country.

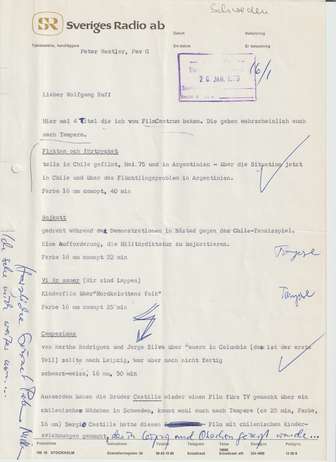

1965

At the 11th West German Short Film Festival Oberhausen in 1965, a flyer[1] circulated that began with a statement by Jean-Marie Straub: "A (West German) Short Film Festival has a meaning only if it helps to discover young yet unknown (West German) filmmakers. Lenica, Kristl, Kluge etc. are not (anymore) to be discovered. Peter Nestler, however, is and has been for the past three years: the truest and most self-assured filmmaker in this country; three of his films, Aufsätze, Mülheim (Ruhr) and Ödenwaldstetten were rejected by the selection committee. So was Thome-Lemke-Zihlmann's very charming (first) film, Die Versöhnung. And there are others."

The flyer accuses the selection committee of having rejected films "whose authors had dared to take reality into consideration,” claiming that the Short Film Festival thus supported a "fashion whose cause is contempt, or stupidity, or helplessness." The flyer was signed by those who were ultimately its subject: in addition to Straub, who had presumably initiated it, the aforementioned Rudolf Thome, Klaus Lemke, Max Zihlmann, and Peter Nestler, as well as those with whom the latter had made his first films: Reinald Schnell, Dieter Süverkrüp, Dirk Alvermann, and Kurt Ulrich.

1965/66

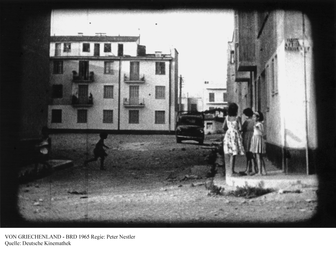

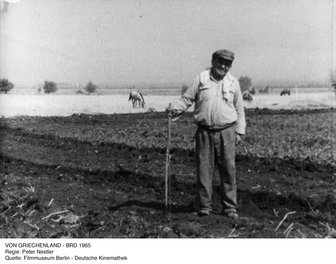

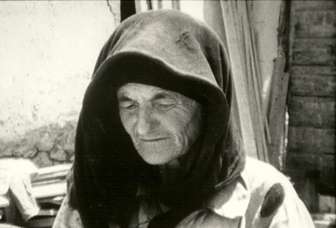

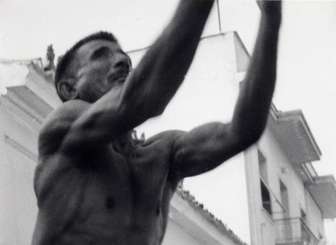

In the summer of 1965, Peter Nestler and Reinald Schnell travel to Greece to document the resistance of the population against the imminent military coup. Their film places current events in the context of the resistance against the German occupation during World War II and the fascist forces that remained powerful in Greece after the war.

In a letter dated February 1, 1966, Will Wehling, the co-director of the Festival, informs Peter Nestler that the selection committee “consisting of Messrs. Haro Senft and Walter Knoop from the Association of Film Producers, Michael Lentz and Dr. Hannes Schmidt from the Association of Film Journalists, as well as the festival management [Hilmar Hoffmann and Wehling himself, T.H.]” was of the opinion that the film he had submitted, Von Griechenland (From Greece), "was not eligible for a competition program after all.” He was pleased, however, to be able to inform Nestler that the film would be part of the German national program, "which will be shown in an evening screening on Wednesday, February 16, 1966.”[2]

“We showed the film in Oberhausen. There was quite a ruckus during the screening. Afterwards, the ʻFilmecho-Filmwocheʼ, the film industry's magazine, called the film a purely communist film.” A verdict not only on the film, but also on Nestler, depriving him of further production opportunities in the FRG. “I tried anyway. I first tried to sell these films that I had made, which were also not shown, and tried to get commissions. And that at every institution, at every station. I didn't succeed. I would have liked to work in West Germany and only went to Sweden because I hoped I could at least continue making films. In West Germany, it was no longer possible for me.”[3]

1967

Peter Nestler emigrates to Sweden where he first works as a lumberjack and then makes a film about the Ruhr region for Swedish television (I Ruhrområdet, 1967). In 1968 Nestler is employed as a commissioning editor at the newly established Second Channel of Swedish television, a relatively stable work situation that subsequently enables him to make "two or three films a year.”[4] In 1968, he makes a short film against the Vietnam War, Sightseeing, to a text by Peter Weiss. The Greek theme continues in Greker i Sverige (Greeks in Sweden, 1968), which Swedish television produces but does not broadcast.[5] From 1969 Peter Nestler's films are made in close collaboration with his wife, Zsoka Nestler.

1970

Correspondence between the directors of the Oberhausen Short Film Festival (Hoffmann and Wehling) and the Cologne film journalist and collector Leo Schönecker[6] in July 1970 reveals that Peter and Zsoka Nestler had apparently submitted their film In Budapest for the 1970 festival and sent a 16mm print to Oberhausen. In the correspondence Schönecker points out that, contrary to the agreement, the costs for the return shipment were charged to Nestler. Schönecker asks the festival to reimburse Nestler for these, which is then ordered in an internal memo. ("Mr. Nestler pointed out that a new print in 16mm format could be struck for the 100 Swedish crowns.") In Budapest was not shown in Oberhausen.

1972/73

In a letter to Will Wehling, dated 22nd Nov, 1972, Sebastian Feldmann[7] suggests that the Oberhausen selectors in Stockholm also watch films by Peter Nestler. He mentions Nestler's then newest films Om Boktryckets Uppkomst (On the Emergence of Letterpress, 1971), Bilder från Vietnam (Pictures of Vietnam, 1972), Om Papperets Historia (On the History of Paper, 1972). At the foot of the letter there is also a handwritten note (by Will Wehling?) indicating that Feldmann also mentioned the film Får de komma igen? (Are they allowed to come back?, 1971), which the commission should "at least watch". "I think it's supposed to be a film about neo-fascism." The note is presumably addressed to Peter H. Schröder and Peter W. Jansen, who went to Stockholm as selectors and received a copy of the letter. None of the films mentioned was shown in Oberhausen. Får de komma igen?, which deals with neo-Nazi structures in West Germany, was a commissioned work for Swedish television, but was removed from the program shortly before the broadcast date and subsequently remained unseen for years.

1973

In the international competition of the Festival, Introduction to Arnold Schoenberg's ʻAccompaniment to a Cinematographic Sceneʼ by Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet is shown as a West German contribution. In the film, Peter Nestler and Günter Peter Straschek read texts by Arnold Schoenberg and Bertolt Brecht. The film had previously received the highest number of votes of all “German” films in the selection committee and was awarded several prizes at the Festival, including that of the German Association of Film Journalists.

1975

Peter Nestler is a member of the International Jury. His film Tyg Del 1 (Cloth Part 1) was initially selected for the competition at the selection screening in Stockholm, but is then shown in a special program because, according to the regulations, films by jury members are not allowed to participate in the competition.

After the festival, Peter Nestler writes a protest statement against the decision of the German Film Rating Board in Wiesbaden to deny the film Protokoll by the Munich group Das Team a rating and thus block its access to a theatrical release. The film deals with the anti-communist motivated "Radikalenerlass" (Decree Against Radicals) of the German government and had been given an honorable mention in Oberhausen by the jury, of which Nestler had been a member. "The view that artistic value can only arise where one gets rid of the political statement is frighteningly reactionary," Nestler wrote in his protest.[8]

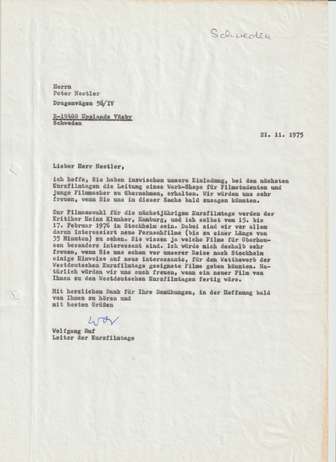

1976

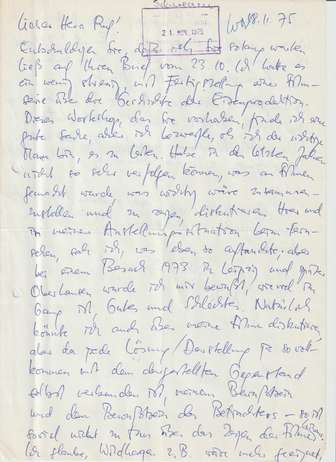

Festival director Wolfgang Ruf invites Peter Nestler to lead a "workshop for film students and young filmmakers" during the 1976 Festival. Nestler replies that he thinks the workshop is a "good thing" but doubts "whether I am the right man to lead it." He feels too distant from what is happening in the FRG because of his permanent position in Sweden, and finally cancels, suggesting others: Klaus Wildenhahn, Rainer Gansera, Helmut Linder, Werner Nekes. He also indicates that he believes "even more in bringing in an expert on the subject matter of the film."

In the course of this correspondence, Peter Nestler mentions that he is currently "finishing a series on iron production" and offers the Short Film Festival the second part of the three-part series in a German version in a letter dated 12/23/75. In the same letter he also mentions the "Series on Foreigners" on which he had already begun to work.

In mid-February 1976, Wolfgang Ruf and Heinz Klunker travel to Swedish television in Stockholm and to the festival in Tampere, Finland, to select films for their upcoming Festival. The yield is meager. In Tampere, they only invite Dialogue by Ole Hedman as a Swedish contribution. Of the TV films, only the ore mining film, Bergshantering / Järnhantering Del 2 (Ore Mining / Iron Production Part 2) mentioned by Nestler convinces them, but they do not want to show it in the competition. Barely back in Oberhausen, Ruf writes to Nestler that he and Klunker "agreed that we could certainly place the film 'somewhere' in the program during the festival." The internal selection report says: "The new television film Ore Mining / Iron Production by Peter Nestler (29 min) was ultimately invited for an informative screening in Oberhausen. We believed that, as in the previous year, continuous information should be provided about Peter Nestler's work, especially in Oberhausen, even if some of his films are not suitable for the competition in terms of their subject matter and their didactic dramaturgy. In addition, Peter Nestler should continue to be involved in the selection work as an important contact person in Stockholm."

The fact that five Swedish films were shown in competition at the 22nd Oberhausen Short Film Festival after all was partly thanks to Peter Nestler's mediation, who called Ruf's attention to a number of films by the independent Swedish distributor Filmcentrum, including the later winner of the "Grand Prix" Campesinos by Marta Rodriguez and Jorge Silva. In addition, the Uruguayan animated film En la selva hay mucho trabajo por hacer (In the jungle there is much to do) by the anonymous Grupo Experimental de Cine screened in Oberhausen in 1976 on Nestler's recommendation, according to later correspondence.

Peter Nestler's Ore Mining / Iron Production Part 2 was shown in a program on April 26, 1976. In the audience was Sebastian Feldmann, who wrote Nestler a postcard afterwards: "Extremely impressed with Ore Mining / Iron Production Part 2 in Oberhausen. I still believe that with this and the other films, a new genre of film (previously only tentatively formulated) has emerged. One should finally be able to see them."[9] On the front of the postcard is a photograph from 1890 depicting a Parisian policeman "immobilizing" a man with a neck grip.

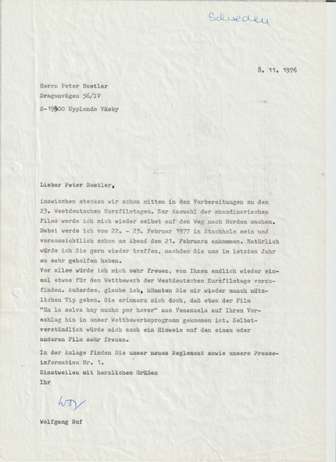

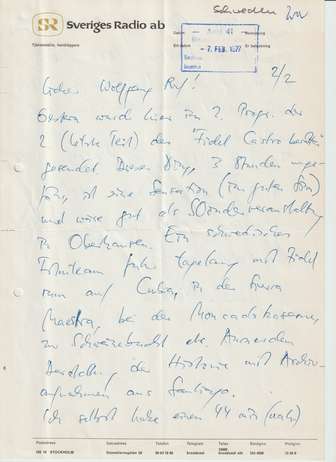

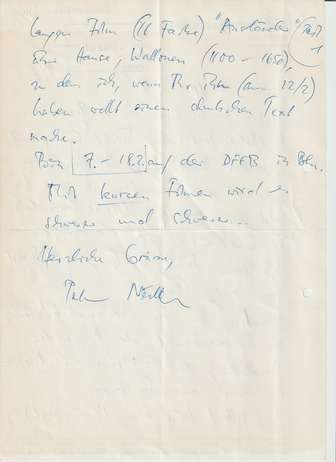

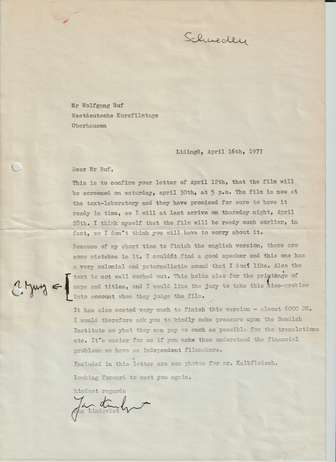

1976/77

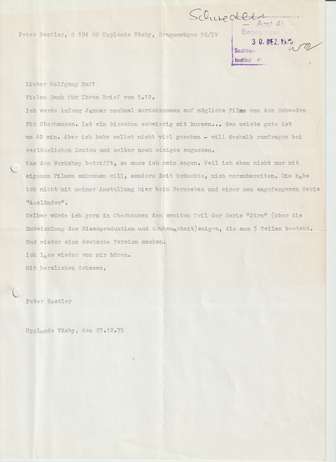

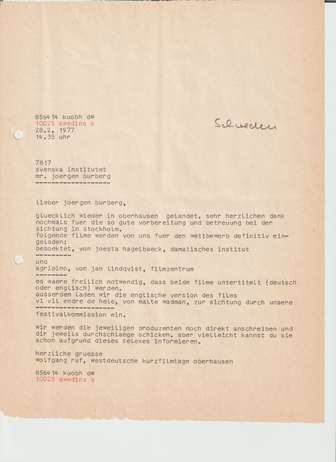

On December 17, 1976, Wolfgang Ruf announces in a letter to Jörgen Burberg of the Swedish Institute the annual selection trip to Stockholm for the end of February 1977. His main concern is a more efficient organization of the screenings: "Returning to your offer to organize the screening of new Swedish short films at your institute, I am enclosing carbon copies of letters to the Swedish Film Centre, to the Dramatic Institute and to the Svenska Filminstitutet with the request to contact the colleagues at these institutes as well. Of course, it would make our work easier if, instead of constantly running back and forth as we did last time, we could view all the films in question at your place. Of course, we would also appreciate it if you could include one or two independent films in the offer. Maybe it would also be good if you got in touch with Peter Nestler, who pointed out to us and actually showed us some films last time."

Three weeks before the announced selection trip, Wolfgang Ruf receives a letter in which Peter Nestler first proposes a three-hour Swedish documentary about Fidel Castro's Cuba for a special program, before he mentions his own "44 min long film (16mm color) Foreigners Part 1 on the Hansa, Walloons (1100-1650)", for which he would - "if you want it" - write a German text. In a terse form letter written in English, Wolfgang Ruf informs Nestler on April 16, 1977 (one week before the start of the Festival) that Utlänningar Del I (Foreigners Part 1) had been viewed and rejected by the selection committee.

This rejection became the subject of an exchange of letters a few months later between Peter Nestler and filmmaker Manfred Blank, who was a member of the staff of the magazine “Filmkritik”. Like Nestler, Blank was friends with Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet, with whom he was making the film Toute révolution est un coup des dés (Every revolution is a throw of dice) in Paris. "The Straubs showed me and Helmut Färber[10] the letter you wrote to them concerning Foreigners Part 1 – Ships and Cannons. In view of the fact that this film had been rejected for Oberhausen, we agreed: something had to be done. Jean-Marie spoke of a note in Filmkritik, Helmut agreed to initiate something. [...] Helmut then contacted Farocki, who, as I heard, wrote to you. The Filmkritik people were then of the opinion that a mere note wouldn't suffice, but that they would like to make an entire Nestler issue, in which the Oberhausen affair could then also be mentioned."

And so it came to pass. In April 1978, No. 256 of the Filmkritik appeared, dedicated to "Peter and Zsoka Nestler" and in particular to their film Foreigners Part 1– Ships and Cannons. It consisted essentially of an illustrated reprint of the film's German voice-over and a text by Manfred Blank entitled "Denkmäler" (Monuments), in which, in addition to an extensive appreciation of Nestler's motifs and his documentary method, he also mentions the film's rejection by the Oberhausen committee. "In 1977, Peter Nestler had wanted to show Ships and Cannons at the West German Short Film Festival in Oberhausen, but the film did not make the program. It had been very long, it was said – I'm quoting this from memory, films longer than 35 minutes could only be accepted as an exception, and besides, there had already been a long film from Sweden, which, by the way, had received the grand prize [Agripino by Jan Lindqvist, T.H.]. The film had also been presented for viewing very late and the jury did not find it that convincing, even though it was quite good. The film fared like 1100 others that had to be rejected. A normal process and not a dark matter, whatever the history of the screening and production of Nestler's films might suggest. There were no reservations about the content."[11]

In the following year, Filmkritik again devoted an entire issue to Peter Nestler. In issue No. 273 (September 1979), various members of the editorial staff wrote personal viewing reports on a total of 18 films by Peter Nestler, i.e. a large part of his complete oeuvre up to that time.

1978/79

Almost as a matter of routine, Festival director Wolfgang Ruf writes to Peter Nestler in Stockholm at the beginning of November 1978: "We are once more in the midst of preparations for our next festival [...] Beatrix Geisel will again be coming to the film selection in Sweden [...] I would be very pleased if there were something from you again for our competition. Surely, however, you could give Ms. Geisel hints about new interesting films." On March 15, Ruf reported to Nestler that after her return from Stockholm Beatrix Geisel had suggested a "special program" of his films, which he found interesting but could not yet confirm.

Beatrix Geisel was apparently suggesting to show in the festival parts 3 and 4 of the "Foreigners" series, in which Nestler addresses the situation of Iranians in exile in Sweden, but also examines the background of their flight and places the policies of the Shah's regime in a historical context. In her selection report, Geisel writes: "[The films] provide a contemporary historical background to the current political events in Iran, beginning in 1900. Nestler uses previously unknown material from Soviet archives, especially in the first part, for example from the oil fields in Baku, which were also of great interest to Nazi Germany." She argues for showing the films by all means "if there is still a corner to be found somewhere," although they were not suitable for the competition "because they absolutely belong together."

In his rejection letter to Nestler of April 14, 1979, Wolfgang Ruf states that they had not found the right place for Utlänningar Del 3 & 4 - Iranier. Apparently Beatrix Geisel had finally suggested in the course of the discussion that the films should at least be shown in the "tradeshows," but this seemed inappropriate to Ruf, since it was an open secret that films shown in the tradeshows were those not considered suitable for competition. "I continue to consider you one of the most important documentarians," he wrote Nestler. "Your film structure (series, multi-part, etc.), conditioned by your work in television, undoubtedly puts our festival in an awkward position at times. Nevertheless, I hope that one of your future films will appear in our competition programme again."

1982

Peter Nestler's Mi Pais - Mitt Land (My Country) is screened in the Festival Competition and is de facto Nestler's first film to which this applies. The film is a wordless memorandum against the Pinochet dictatorship in Chile, composed of images and music by four Chilean artists in exile.

1983

In the "Filmothek der Jugend" (the youth film festival that has accompanied the Short Film Festival since 1969) Peter Nestler's Hur förtrycket slår (The Consequences of Oppression, literally: How Oppression Strikes) is shown, another film that deals with Pinochet's now ten-year rule in Chile and examines its psychological effects on children. In August 1983, Wolfgang Ruf recommends the film to a public education institution in Mülheim/Ruhr and a media festival in Frankfurt/Main for their respective planned film programmes on Chile.

1986

For the second time a film by Peter Nestler is shown in the Festival Competition: Väntan (The Wait), in which Nestler uses photos from a Swedish archive to tell the story of a mining accident that occurred in Lower Silesia in July 1930.

1990

In her first year as director of the Festival, Angela Haardt appoints Peter Nestler to the International Jury chaired by the Egyptian filmmaker Atteyat el-Abnoudhy. Väntan is screened once again in the festival's opening programme. The jury awards the main prize to Alexander Sokurov's Sovietskaya Elegia. It is mainly thanks to the encouragement of Peter Nestler and his jury colleague Bela Tarr that the Iranian film Bareha Dar Barf Bedonya Miayand (The Lambs Are Born in the Snow) by Farhad Mehranfar also receives a prize (and thus remains in the festival archive), namely the "Environmental Prize", donated by an Oberhausen citizen, which was awarded for the first and only time in that year.

--

The present text would not have been conceivable without the openness and generosity of Peter Nestler. I thank him very much for this. Likewise to my colleagues in Oberhausen, who have accompanied my research in the festival archives with trust and interest since 2018: Lars Henrik Gass, Martin Gensheimer, Chris Schön, Carsten Spicher, Katharina Schröder, Barbara Schulz.

Footnotes

[1] First published within a festival report by Michel Delahaye in Cahiers du Cinéma (April 1965). Republished in German in Ralph Eue, Lars Henrik Gass (eds.): Provokationen der Wirklichkeit - Das Oberhausener Manifest und die Folgen (Munich, 2012) and in Danièle Huillet, Jean-Marie Straub: Schriften, eds. Tobias Hering, Volko Kamensky, Markus Nechleba, Antonia Weiße (Berlin 2020).

[2] The letter quoted is in Peter Nestler's private archive. It is not archived in Oberhausen. The “Information Programme I - Films from Germany (out of competition)” began at midnight and, in addition to From Greece, included films by Klaus Lemke, Jeanine Meerapfel and Hellmuth Costard, among others.

[3] “Arbeiten beim Fernsehen in Westdeutschland und Schweden” [Working for television in West Germany and Sweden], Peter Nestler in conversation with Gisela Tuchtenhagen, Klaus Wildenhahn and Angelika Wittlich, Filmkritik No. 224 (August 1975).

[4] ibid.

[5] see “Filmographie in Daten”, in: Zeit für Mitteilungen – Peter Nestler. Dokumentarist, ed. Jutta Pirschtat (Filmwerkstatt Essen, 1991), p. 187.

[6] For decades, film collector Leo Schönecker in Cologne was the most reliable source for distribution copies of Nestler's films in Germany. Even today, the catalogue of the “Filmkundliches Archiv Leo Schönecker”, which still exists, lists distribution copies of thirteen of Peter Nestler's films. A Peter Nestler exhibition at the Kino im Sprengel in Hanover in 2018 was exclusively presenting prints from the Schönecker archive at Nestler's request. The official distributor for Nestler's complete oeuvre in Germany is now the Stiftung Deutsche Kinemathek in Berlin, where his films have been digitally restored in recent years, including most of his Swedish productions, which are still less well-known in Germany.

[7] Feldmann was a German film journalist who advised the Oberhausen Short Film Festival on the selection of Scandinavian films. In 1972 he was also part of the organisational management of the Festival. In the same year, Feldmann published the essay "Learning from Water - Peter Nestler: An Aesthetics of Poverty" in the magazine Filmkritik (No. 186, June 1972), which was possibly the first such thorough journalistic appreciation of Peter Nestler's films in Germany.

[8] Typescript of the protest statement in Peter Nestler´s private archive.

[9] Private archive, Peter Nestler.

[10] Helmut Färber had been part of the editorial staff of Filmkritik since the early 1960s and was one of the magazine´s most active writers. He was also a close friend of Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet and, like Manfred Blank, one of the speakers who, in their film, Every revolution is a throw of dice, sit on a lawn of the Père Lachaise cemetery in Paris and recite Mallarmé's poem "Un coup de dés jamais n`abolira le hasard".

[11] Manfred Blank, “Denkmäler”, in: Filmkritik, No. 256 (April 1978), p. 203.

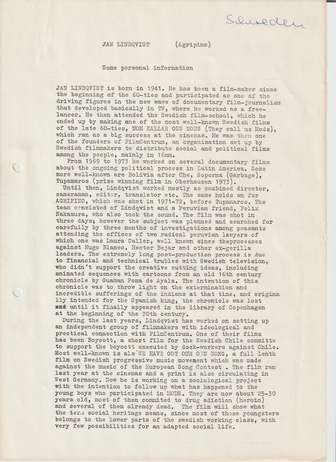

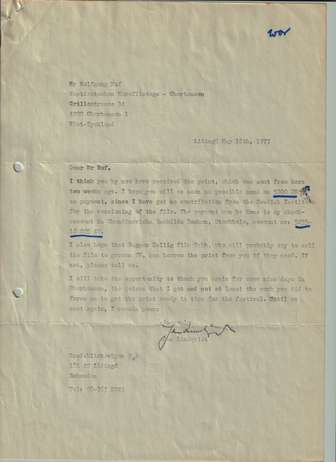

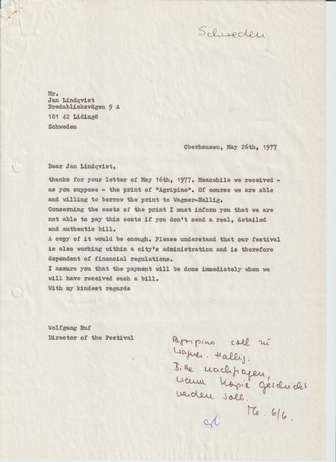

Two Films by Jan Lindqvist

by Tobias Hering

There are two films by Jan Lindqvist in the archives of the Short Film Festival Oberhausen: Tupamaros (1972) and Agripino (1977). Both have been preserved as 16mm colour prints with English subtitles; Agripino also has an English voiceover commentary. They are both still in decent condition for their age, with the colours in Tupamaros having faded more than those in Agripino.

The presence of the two copies in Oberhausen is not surprising, since both films were awarded main prizes by official juries at the festival, which, as set forth in § 17 of its regulations, normally led to the purchase of the festival copy or of a new one. Tupamaros screened at the 19th West German Short Film Festival in 1973 and won the FIPRESCI Jury Prize (in a tie with The Machine by Helma Sanders) as well as (in a tie with Heuwetter by Gitta Nickel) the Jury Prize of the “Association International du Film Documentaire” (AID), awarded for the first time that year.[1]

Agripino was shown at the 23rd West German Short Film Festival in 1977 and was awarded the “Grand Prize of the City of Oberhausen,” endowed with 5,000 DM, by the International Jury, the FIPRESCI Prize (2,000 DM), as well as the INTERFILM Jury Prize, which came with a 2,000 DM grant. This meant that, all in all, Jan Lindqvist went home with 9,000 DM in prize money, which is remarkable also in light of the fact that in the run-up to the festival, the high cost of the English festival copy of the film, which had been made under time pressure, had been a problem.

The lending lists for both films indicate typical demand in the months after the festival, later followed by sporadic interest from political education institutions and film schools, distributors, cinemas and other festivals. As prize winners, both copies went on a one-time tour with the festival directors of those years (Will Wehling and Wolfgang Ruf, respectively). Tupamaros traveled to Japan in October 1975, Agripino to Moscow in June 1977, a year later to Cuba and in the fall of 1983, with representatives from the Federal Foreign Office, to Ecuador. Both copies were shown once at the Mülheim Adult Education Center, near Oberhausen, in the spring of 1983.

The Oberhausen archives include extensive correspondence regarding Agripino; for Tupamaros, on the other hand, I have so far only been able to find two letters there, neither of which is particularly significant: the carbon copy of a letter dated February 12, 1973 and addressed to Anna-Lena Wibom at the Svenska Filminstitutet (where the Swedish selection screening had just taken place), in which festival director Will Wehling confirms the selection of Tupamaros, even though the film “is longer than 36 minutes” (the official maximum running time for competition films); and a telegram, presumably also addressed to Wibom, in which Wehling at the end of the festival reports that the film has been awarded a prize and urgently requests permission to add the copy to the “archive of award winners.” He adds: “If desired, we will cover lab costs.”

Tupamaros was shown in the opening programme of the 1973 festival, entitled “Freedom for Carlos Álvarez” and intended as a gesture of solidarity for the filmmaker, who was imprisoned in Colombia at the time. Besides Tupamaros, the two-and-a-half-hour programme included Chircales – The Brickmakers by Marta Rodriguez and Jorge Silva (Colombia), Pueblo de Lata by Jesús Guédez (Venezuela), a documentary about the recent U.S. bombardment of Hanoi – presumably a newsreel, which, however, I was not able to identify definitively –, as well as Introduction to Arnold Schoenberg's Accompaniment to a Cinematic Scene by Danièle Huillet and Jean-Marie Straub. All the films were shown in competition that year except for the Vietnam War documentary.

It would not have been surprising if Tupamaros had given rise to controversy in the selection committee. For Lindqvist to take sides with an armed guerrilla struggle must have come across as provocative in 1973 West Germany and would not have gone unnoticed at an event with the political profile of the Oberhausen Short Film Festival. Three years prior, in May 1970, the terrorist Red Army Faction (RAF) had appeared on the public scene for the first time when some of its members had helped Andreas Baader escape from police custody in a spectacular break-out. Since then, armed struggle (in RAF parlance, “people's war”) had occupied political fantasies on both the right and the left. The RAF strategy of “urban guerrilla warfare” explicitly invoked Latin American models, the most prominent of which were the Tupamaros. A multi-page position and strategy paper, which appeared shortly after the spectacular Baader liberation in May 1970 in “Agit 883,” a pamphlet put out by the radical left scene in Berlin, included a call for armed resistance and the establishment of the “Red Army.” This is considered to have been the first published statement by the RAF. On the pamphlet’s front page, the names of five international groups with which the militant scene identified are arranged around a star; one of them is the Tupamaros.

While these first cues were still directed at the narrower circle of RAF supporters, hostage-takings, bombings and bank robberies in the following two years ensured that a broad West German public came to know about the group and increasingly felt directly affected – probably less by the terrorists’ actions themselves than by the increasingly extensive measures taken by state security agencies in their manhunt, which targeted a large number of innocent people and were thus extremely controversial. For years, wanted posters with photos of suspected RAF members were displayed in every West German public building. In early June 1972, following a large-scale nationwide operation involving roadblocks and dragnets, the police made numerous arrests, including those of the then suspected leaders of the RAF: Jan-Carl Raspe, Holger Meins, Andreas Baader, Gudrun Ensslin and Ulrike Meinhof. The operation was preceded by the RAF's “May Offensive,” a series of bombings at police stations, court houses and U.S. Army installations, in which four people were killed and over 70 injured.

Given this context, we can assume that when Jan Lindqvist's film was shown in Oberhausen a year later, a statement of sympathy for the Tupamaros and underground armed struggle was extremely provocative. The fact that the film was shown anyway (possibly even without having led to major discord) and received two prestigious prizes perhaps speaks to the political independence that the festival had already established for itself, but possibly also to the acceptance that armed struggle had at the time, if not as a necessary means, then at least as a political fantasy – or at least to a broad willingness to engage with the question of militancy.